The start of my childhood development course has taken me down the alleys of thinking about how it is exactly that children develop and what it is that affects their development. History has seen many a theory being introduced to explain how it is that we develop, learn, and grow. Not all of them still fully apply today, and some seem absolutely baffling if you’re not inclined to share the views of those who first introduced them. But on the whole, most of them have good points that seems to work especially well when mixed and matched in between the different theories.

The start of my childhood development course has taken me down the alleys of thinking about how it is exactly that children develop and what it is that affects their development. History has seen many a theory being introduced to explain how it is that we develop, learn, and grow. Not all of them still fully apply today, and some seem absolutely baffling if you’re not inclined to share the views of those who first introduced them. But on the whole, most of them have good points that seems to work especially well when mixed and matched in between the different theories.

The four I studied in-depth seemed to grow from within one another, with obvious elements of past theories being dropped as new and shiny concepts are introduced. Sometimes the progress is minimal, sometimes it is revolutionary, but each step taken forward towards a more global understanding of childhood development is an important one: full of promises of better parenting, happier children, and better developed adults. But there is a debate that has always permeated theories of development: are we the product of nature, or the product of nurture?

It’s not just psychologists that have been faced with this headache, and philosophers have, for centuries, asked themselves the same question. To clarify the terms, nature refers roughly to what we are given at birth: our DNA. Nature will decide if we have blond or brown hair, blue or grey eyes, whether our knees are not aligned or we are likely to get coldsores. Nurture, on the contrary, does not come to us with birth, but through the social context in which we are born, through the people around us, through the education we receive, and so on and so forth. So nurture isn’t going to decide what colour hair we have, but it is likely to decide what kind of human being we grow up into.

To an extent.

And this is where it gets tricky. Once we are grown adults, how can we pretend to know how and why we have turned out as we have? We can make guesses, theorize, look back on our childhood and try to make rational, logical sense of it in a way we couldn’t at the time. But at the end of the day, even through careful study of other children, there is no sure way to draw solid conclusions and form theories that could claim to apply universally (because humans, after all, have this awful tendency to all be so very different from one another).

Take, for example, the case of Alfred (Yes, this is the best name I could up with for my made-up example). Alfred was born in a loving home, surrounded by a loving, peaceful family. He never spent ridiculous amount of hours watching violent programs on TV either. And yet, Alfred was a violent, anti-social child who could hardly be controlled by his parents. Eventually, it was discovered that Alfred had been born with a deficient part of his brain and was in fact a psychopath Here, nurture is absolutely powerless against nature, although there is no doubt the nurturing would have affected Alfred in some ways. But nonetheless, who Alfred grew into was not ruled by nurture, but by nature. Perhaps even by both for who can say how Alfred would have turned out had he been raised away from a loving and understanding home? Nobody can, and that’s why the nurture vs nature debate is such a tricky one.

Obviously, there are times when nurture can influence nature, or at least can seem to. Children who are unruly from a young age can be taught discipline, but it is difficult to know whether their unruliness is something that they were born with (an innate trait of character) or whether it something they picked up from peers or siblings behaviour. What, however, of children who demonstrate such behaviour without ever having witnessed it from others? Are they born with an innate desire to be unruly and cause havoc? Perhaps. And if that is the case then nurture can indeed overrule (or perhaps more so, bend and modify) nature.

Another issue with the concept is when we start looking at people’s choices in career. Those who follow artistic careers and have had contact with an adult they are related to who also follows such a career might find they are told that they are doing so that it is because it is in their nature (clearly being a musician runs into the family, for example). But if a child of two doctors follows the same line of work as his parents, people are far more likely to blame it on nurture (it’s all he’s ever known/he’s trying to be like you). The question is, what is the difference? Maybe a child only chooses to become a musician, not because it is somehow written in his genes, but because he wants to be like his father, his mother, or his uncle. And maybe the little girl whose parents are doctors decides to follow in their footsteps not become she dreams of being like them, but because she feels a real calling towards the profession.

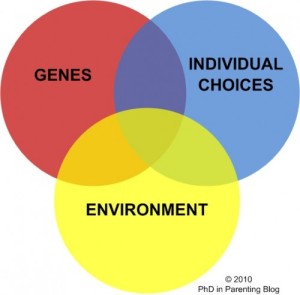

Either way, the idea that either nature or nurture forms us into what we become misses out one important factor: choice. Neither theories, not even them combined, take our own personal choices into account. From a very young age, babies and children are capable of making choices in their day-to-day lives and those choices are likely to have as strong an impact on their development as nurture and nature put together. But that’s for a different blog post all-together.

Psychologists are more and more agreeing that pitching nature vs nurture is a terrible idea and that if we are to truly understand how we develop, both as children and once we have reached our adult years, we need to look at both. To understand one truly would mean the need to understand the other just as completely. Indeed, how could there be development as we know it if only nurture, or only nature had a part to play?